Weaving Space: Identity, Memory, and Resilience in the Art of Qinza Najm

- Qinza Najm

- Abigail MacFadden

- April 21, 2025

- 6 min read

In the exhibition "Weaving Space," artist Qinza Najm invites viewers into a deeply personal exploration of identity, memory, and resilience through striking works hand painted directly onto reclaimed Persian carpets—not just any carpets, but ones the artist herself has lived with, sat upon with family and friends, and carried through her own personal journeys. These intimate textiles serve as both medium and message, transforming everyday domestic objects into powerful vessels of cultural memory and personal narrative, while the geometric, gem-like forms painted onto them create a visual tension between erasure and visibility, beauty and rupture.

In the following conversation, Qinza Najm herself discusses her creative process, the emotional architecture she constructs through her art, and how her background in psychology and experiences as a Pakistani-born immigrant in New York have shaped her artistic vision. Through this intimate dialogue, we gain insight into how Najm elevates once-walked-upon textiles to eye level, challenging viewers to reconsider what—and who—society often overlooks, while weaving together threads of her own lived experience into a powerful artistic statement about belonging, identity, and transformation.

Go see her show for the closing event on Tuesday April 22 at Art Gotham in New York City.

Abbey: Can you tell us about Weaving Space and the core themes of this exhibition?

Qinza: Weaving Space is a deeply personal inquiry into how identity, memory, and resilience are held—and sometimes hidden—within material, gesture, and form. The title speaks not just to textile, but to the emotional and psychological act of holding contradictions together. As someone who has moved between cultures and cities my whole life, I’ve often had to build an inner architecture of belonging wherever I land. This show reflects that process.

At the center are large-scale works painted directly onto reclaimed Persian carpets. These are not just surfaces—they’re vessels of cultural memory, often walked over or dismissed, much like the stories of women and migrants. By painting geometric, gem-like forms onto them—symbols of pressure, value, and transformation—I’m creating a visual tension between erasure and visibility, beauty and rupture. The gems shimmer but never fully resolve. They float, fracture, and resist.

There are also smaller, quieter works—on canvas and wood—that echo these themes through texture, collage, and fragmentation. Whether working with textiles, paint, or salvaged materials, I’m asking how we carry history in the body and in the spaces we inhabit. What is swept under the rug, what is stitched into us, and what insists on being seen?

Weaving Space invites viewers into that in-between: between tradition and reinvention, between grief and becoming. It's about finding clarity—however fractured—within the noise of migration, memory, and making.

Abbey: How has your background in psychology (and a PhD focused on emotional intelligence) influenced your art practice?

Qinza: As someone with a Ph.D. in psychology, particularly focused on emotional intelligence, my work is rooted in the nuanced, often invisible terrain of human behavior and feeling. Weaving Space is a culmination of that inquiry—a visual field where personal memory, social rupture, and collective longing are layered, excavated, and transformed. My training taught me how we internalize trauma, how silence operates, and how empathy can create openings even in fractured systems. I carry this into my studio practice—not as theory, but as an embodied way of listening.

The gem-like geometries in this series aren’t just visual motifs; they are metaphors shaped by emotional pressure. In psychology, as in geology, transformation often occurs under force—through fracture, tension, and resilience. My mother used to say, “Become a diamond. Every cut makes you stronger.” That stayed with me. These faceted forms float over distressed surfaces like psychic imprints—remnants of the subconscious, trying to reorganize chaos into something luminous.

The carpets, weaved and hand painted over, hold another layer of meaning. These aren’t just materials; they’re sites of projection—vessels for cultural memory and emotional inheritance. In psychological terms, they’re spaces where private pain and public history meet. Much like therapy, my paintings hold contradictions: rupture and repair, clarity and confusion, vulnerability and power. What I try to build is a kind of emotional architecture—where viewers can sense, even if not immediately name, the depth of what’s been carried, concealed, or finally made visible.

In a world increasingly defined by fragmentation, I use abstraction not to obscure, but to reveal—to make space for empathy, tension, and complexity to coexist. That, for me, is the heart of both psychology and art.

Left: Red Gem, White Smoke, 2025, Qinza Najm and Right: Red Gem, 2025 Qinza Najm

Abbey: As a Pakistani-born immigrant living in New York, how does the experience of displacement or living between cultures inform your art?

Qinza: My relationship with displacement began long before I crossed any borders. As the daughter of an Air Force pilot, I grew up moving every two years across Pakistan—never quite settling, always recalibrating. Home became an ephemeral thing: a state of mind, a feeling carried rather than possessed. That early nomadism shaped how I see the world, and it continues to shape my work. For me, art is not just a medium; it’s a survival tool, a mapping of the invisible threads that hold us together as we move through rupture, longing, and reinvention.

As an immigrant in New York, I found that tension between belonging and unbelonging deepen. Here, I’ve had to rebuild identity from fragments—language, memory, culture—while embracing the brutal clarity and freedom that this city demands. My art reflects that duality: the rootedness of heritage and the restlessness of reinvention. The carpets I paint on are more than materials—they are carriers of memory. Historically, carpets were not only decorative but nomadic: carried from place to place, gifted, slept upon, prayed on. They hold footsteps, silences, and secrets. By lifting them onto the wall, I’m challenging the notion of what gets walked over—who gets walked over—and turning that narrative on its head.

My hope is that someone standing in front of my work – whether they’ve migrated across continents or just across town – feels that delicate balance of loss and discovery. I want them to sense the complexity of finding home within yourself, and to recognize that our identities are mosaics of all the places and cultures we carry.

Abbey: Your work often incorporates salvaged Persian carpets and other everyday materials. What draws you to these materials, and what role do they play in your art?

Qinza: I have a deep love for working with salvaged materials – especially old Persian carpets. There’s something poetic about a carpet: it holds so much memory. A carpet is walked on daily, bearing the footprints and stories of people, yet in many cultures it’s also a treasured heirloom or a sacred object (think of prayer rugs). That contrast fascinates me. By cutting up a used carpet and integrating it into my art, I’m both honoring and subverting its traditional role. I’m literally lifting it off the floor – where it might be overlooked or trampled – and placing it at eye level for contemplation. This transformation turns a carpet from something utilitarian into something almost reverential. It’s my way of saying that the stories of ordinary people – the ones who trod on that rug, the hands that wove it – deserve to be seen and valued.

Beyond carpets, I use other everyday materials like old wooden trunks or fabric scraps. This process of material transformation – turning the humble and discarded into something evocative – is central to my practice. Each carries its own history. For example, when I repurpose a Persian carpet, I’m tapping into a rich heritage of craft and storytelling. Working with textiles reminds me of my grandmother’s home, yet I present it in a contemporary, disruptive context. That mix of respect and rebellion fuels me. The resulting artwork becomes a meeting place of past and present. I hope it makes viewers reconsider these familiar objects – to see, say, a carpet not just as décor, but as a witness to history and a carrier of untold stories.

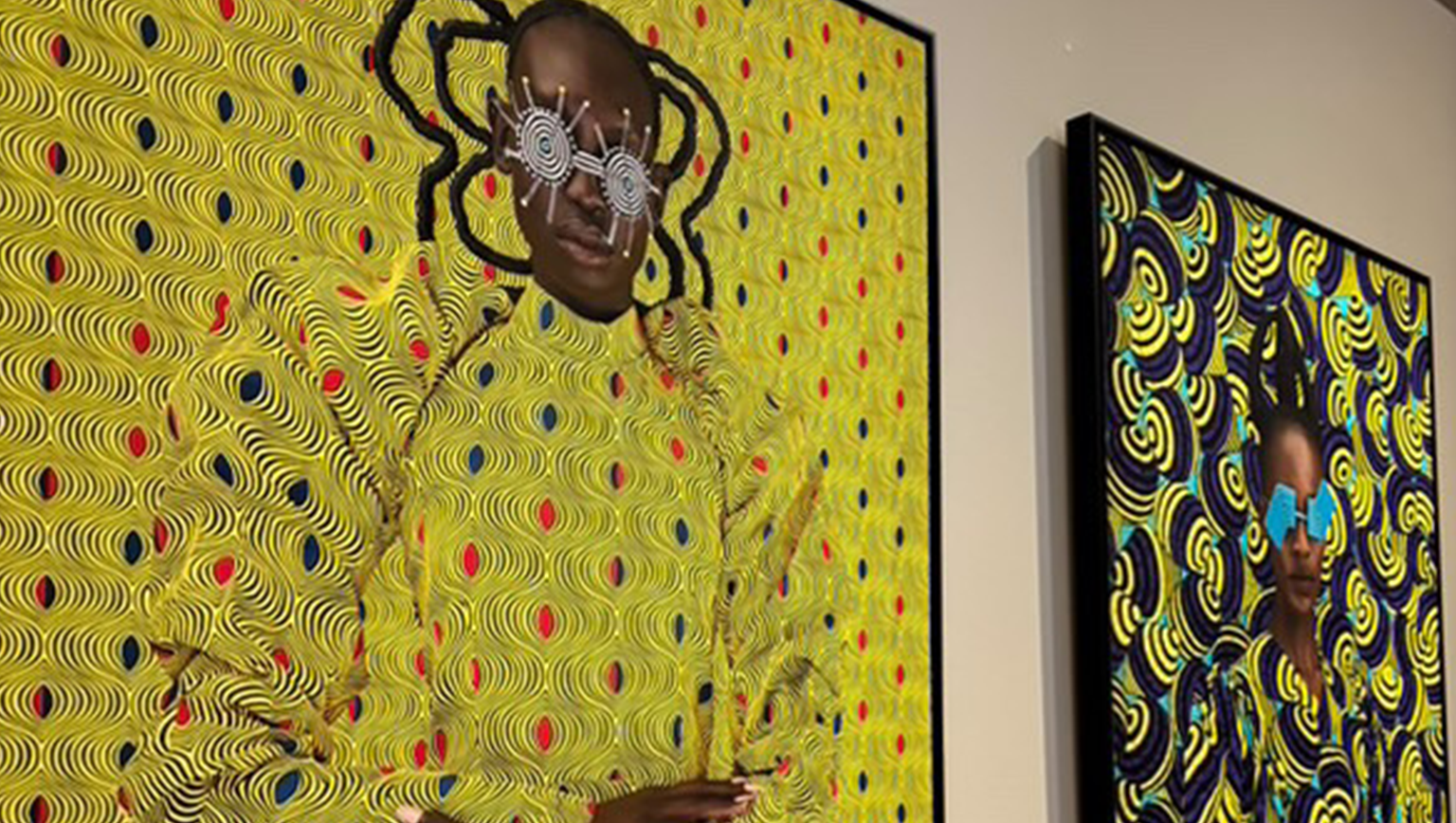

Closest Painting on Right: Grey Swirl, 2025 Qinza Najm

Abbey: Many of your paintings feature geometric, gem-like forms. What do these gem shapes represent in your work?

Qinza: Ultimately, these forms are about visibility. They ask: What do we consider precious? What do we hide or inherit? And what do we allow to shine, even after being shaped by fire?

The gem forms in Weaving Space are not just visual motifs—they’re emotional anchors, metaphors for resilience, erasure, and survival. They first appeared in my work nearly a decade ago, and after a long silence, they’ve returned with greater urgency. I didn’t plan their reemergence—they resurfaced organically, almost like a memory needing to be processed again, this time with more clarity and conviction.

Gems are formed under pressure, cut and polished to reveal their worth. That alchemical process mirrors the emotional and social shaping many of us go through—especially women, immigrants, and those whose stories are often ignored or silenced. My name, Qinza, means treasure. And perhaps these forms are a way of reclaiming that idea of value—on our own terms.

In this show, the gem shapes float against distressed fields of pigment or over hand-painted Persian carpets. On canvas, they rise from abstraction and rupture. On the carpets, they interrupt pattern and tradition, weaving new meanings into inherited materials. These carpets, historically walked on, sometimes discarded, become sites of transformation—where the sacred and the overlooked meet. Painting on them is a quiet rebellion against cultural erasure and a gesture of reverence for the stories they carry.

To me, these gems don’t represent perfection—they hold complexity. Some are fractured, others asymmetrical. They exist between order and chaos, clarity and shadow, much like the identities I explore. They are about taking up space—psychic, emotional, and literal—and resisting the instinct to hide or minimize. They ask: What do we treasure? What has been swept under the rug? And what happens when we dare to lift it back into view?

Ultimately, the gem is a visual language I return to when I need to reclaim power, memory, and presence. It’s not a recurring motif in my work—it’s a deliberate one, shaped by time, context, and the desire to turn invisible histories into something that can shine.

Abbey: You push the boundaries of abstraction while still conveying narrative and Larry Poons influence your style?

Qinza: My approach to abstraction has always been deeply tied to emotion and storytelling—it’s never just been about form or gesture. Studying under Larry Poons at the Art Students League was pivotal. He taught me to trust instinct, to pour without fear, to understand that abstraction could carry emotional weight without needing to explain itself. From him, I learned not just technique, but a kind of artistic bravery—permission to push, to make a mess, to feel through the canvas. But over time, I also found that I wanted abstraction to do something more: to carry memory, cultural friction, and lived experience.

I come from a place—Pakistan—where stories are woven into everything: carpets, gestures, lullabies. When I moved to New York, that visual language of abstraction became a bridge between my inherited culture and my present self. I began embedding narrative symbols into my abstract works—not literally illustrating, but integrating traces: a gem form, a trunk, a carpet motif. These are not decorative—they’re anchors. They hold weight.

In Weaving Space, this balance comes into full focus. The raw energy of abstraction—poured paint, fragmented geometry—meets the intimacy of memory and metaphor. My process now is part emotional excavation, part intuitive movement. Abstraction is still a space of freedom for me, but it’s also a map—layered, textured, imperfect—of all the places, identities, and contradictions I carry.

From Left to Right: Stretched earring, 2025 and Stretched Klimt, 2025 by Qinza Najm

Abbey: Gender and cultural norms are themes that surface in your work. How do issues of gender, particularly the female experience, play a role in your art?

Qinza: As a Pakistani-born woman navigating life between Lahore and New York, I’ve lived within—and pushed against—the layered expectations of gender my entire life. My work emerges from that space: not as a reaction, but as an excavation. I’m interested in the quiet architecture of womanhood—how we’re taught to carry, to withhold, to adapt—and what happens when we make that inner weight visible.

The materials I use are intentional. Reclaimed carpets, domestic textiles, and ornate patterns often associated with the feminine are transformed—elevated from the floor to the wall, from background to center. These materials, like women, are often walked over, sentimentalized, or rendered invisible. By recontextualizing them, I’m honoring their history while also challenging it.

The faceted gem forms that recur in Weaving Space carry similar weight. They're luminous, sharp, and resilient—qualities women are expected to embody without ever showing the pressure it takes to hold those forms. I rarely paint these gems perfectly; they’re fractured, suspended, sometimes veiled. They speak to survival, not spectacle. Their clarity is forged under pressure, just like our own.

My work doesn’t aim to declare answers, but to hold space for contradiction—the grace and the grit, the seen and unseen. Whether it’s through abstraction, texture, or material, I’m always asking: What have we been taught to conceal? And what becomes possible when we no longer do?

Abbey: Your art deals with visibility, history, trauma, and the idea of reclaiming narratives. How do you approach these heavy themes and what do you hope to convey?

Qinza: I often think of my work as a quiet unearthing. It’s less about making bold declarations and more about gently revealing what has been overlooked—whether personal memories, inherited silences, or cultural histories. Growing up between Lahore and New York, I’ve always felt surrounded by layered stories: the things we carry, the things we lose, and the things we’re taught not to say out loud.

In Weaving Space, I’ve worked with salvaged materials like Persian carpets and textiles because they already hold so much history. These materials are familiar, domestic, sometimes intimate—and by painting on them, I’m trying to bring new attention to the lives and experiences they represent. Often, I’ll bury fragments beneath the surface or let certain parts fade, the way memory does. The goal is not to recreate the past, but to make space for it—to let it breathe and be seen differently.

At the same time, I’m always thinking about healing. I want my work to hold the tension between what’s difficult and what’s possible—between loss and resilience. It’s not about answers, but about making room for reflection, empathy, and a sense of connection. If someone sees part of their own story—or someone else’s—with new clarity through my work, then I feel it’s done what it needed.

From Left to Right: Yellow Gem, 2025 and Blue Gem, 2025 by Qinza Najm

Abbey: In addition to being an artist, you’ve worked as a curator. How has curating and collaborating with other artists influenced your perspective?

Qinza: Curating Mana Art Now was my first time officially stepping into a curatorial role, and it felt incredibly meaningful—especially as someone who recently joined the Mana Contemporary community. It was both an honor and a priority for me: to get to know the artists around me, to understand their practices, and to create a shared space where our voices could be in conversation. I didn’t want to just be in a studio bubble—I wanted to listen, connect, and offer visibility to others whose work deserves to be seen and felt.

What surprised me was how curating also changed my lens as an artist. I started thinking differently about spatial relationships, pacing, and how individual works speak to memory, tension, or silence when placed together. It wasn’t just about selecting strong work—it was about creating an atmosphere, a kind of rhythm. That has absolutely fed back into how I think about installing my own pieces.

This experience also deepened my belief that art doesn’t exist in isolation. My work has always been rooted in community, in listening, and in dialogue. Curating just gave me a new way to extend that. And I’m grateful to Kimberly, the gallerist at Art Gotham, for trusting me with that space. It’s reinforced my commitment to building not just a career, but a creative ecosystem where mutual respect and collaboration thrive.

Abbey: Your practice spans painting, performance, and installation. Why is it important for you to work in such a multidisciplinary way?

Qinza: I begin with painting, but the questions I ask often outgrow the canvas. Some stories need movement, others need space or physical presence. When I created Tabdeeli, a performance with seven dancers, or #NoHonorInKilling, where I wore bullets as a second skin, the body itself became the message. My installations—like stitched Payti trunks or carpets embedded with gem-like forms—carry memory and material history in a different way.

Each medium allows me to express a different emotional register. Together, they create a fuller, more textured narrative. I don’t see this as switching languages—I see it as deepening one conversation. Whether through gesture, space, or object, I’m always trying to create experiences that hold complexity and invite reflection.

Don't miss the rare opportunity to experience Weaving Space in its final days and join us for a special closing event on Tuesday, April 22, from 6-9pm at Art Gotham in New York City, where Qinza Najm will share deeper insights into her creative process, the emotional landscapes she navigates through her art, and the personal journeys that have shaped these powerful works—an intimate evening that promises to illuminate the invisible threads connecting migration, memory, gender, and cultural identity that form the foundation of this extraordinary exhibition.

Closing Event: 6-9pm, Tuesday, April 22, 2025, Art Gotham, 4 St. Marks Place, New York, NY 10003

Link to Artist Profile

Qinza Najm: :

Read More

Mary J Blige’s “For My Fans” Tour: A Love Letter to Three Decades of Hip-Hop Soul

Sasha Bernier • April 16, 2025 •

5min read

Together We Art Fair: A Celebration of Interconnectivity in New York

Abigail MacFadden •April 14, 2025 •

6 min read

Grace Chen: china's power dresser blending east and west

Abigail MacFadden •April 11, 2025 •

5min read

Read More

Mary J Blige’s “For My Fans” Tour: A Love Letter to Three Decades of Hip-Hop Soul

Sasha Bernier • April 16, 2025 •

5min read

Together We Art Fair: A Celebration of Interconnectivity in New York

Abigail MacFadden •April 14, 2025 •

6 min read

Grace Chen: china's power dresser blending east and west

Abigail MacFadden •April 11, 2025 •

5min read

Sculpting Dreams in Silk: The Couture of Sohee Park

Chiara Padejka • March 31, 2025 •

5min read

Living Art and Orchids: A Breathtaking Journey Through Mexican Design at NYBG

Abigail MacFadden •March 28, 2025 •

5 min read

Dieter Roth. Islandscapes shines at Hauser & Wirth during IFPDA week

Abigail MacFadden •March 26, 2025 •

5min read

Who is the Gong Girl? Mark Gong’s Global Muse

Chiara Padejka • March 25, 2025 •

5min read

Rhyme with Reason: Irish Tapestry Studio puts Sustainability First

Chiara Padejka •March 19, 2025 •

6 min read

WAX: The African Fabric at the Heart of Fashion and Art

Lara Sleiman •March 18, 2025 •

5min read

Grasslands: The Afrofuturistic Journey of Mwinga Sinjela’s Artistic Evolution

Abigail MacFadden • March 17, 2025 •

5min read

Person Place Thing : The Building Blocks

Chiara Padejka •March 14, 2025 •

5 min read

Australian Visions: Coma Gallery Makes Impressive Debut at Felix LA

Tess Azcuna •March 11, 2025 •

5min read

Colombian Magic at Nohra Haime Gallery

Abigail MacFadden • March 7, 2025 •

5min read

Beyond the Box: Tiffany Lamps and the Legacy of Artistry

Chiara Padejka •March 6, 2025 •

4min read

Tess Azcuna: Bridging Worlds in Entertainment, Fashion, and Business

Abigail MarcFadden •March 4, 2025 •

4min read

Maria Paula Suarez: The Alchemy of Emotion

Abigail MacFadden • March 4, 2025 •

5min read

Vibrant Artistry and Bold Commentary: Victor "Marka27" Quiñonez Wins Frieze Impact Prize

Abigail MacFadden •MArch 3, 2025 •

5min read

Lorenzo di Medici’s “Renaissance Pop” Collection Shines at LA Art Week

Sasha Bernier •March 3, 2025 •

6min read

Felix Art Fair: An Intimate Art Experience at the Roosevelt Hotel

Sasha Bernier • February 26, 2025 •

5min read

Stories Unfolding: A Tapestry of Narratives at Art Gotham

Abigail MacFadden • February 24, 2025 •

5min read

Standout Showcases: Six Must-See Galleries at Frieze Los Angeles 2025

Abigail MacFadden • February 23, 2025 •

6min read

Gagosian’s "Nomadic Folly" Offers Peaceful Respite During Los Angeles Art Week 2025

Abigail MacFadden • February 23, 2025 •

4min read

"Evidence of Us": Marie Chloe Duval's Floral Meditations on Time and Memory

Abigail MacFadden • February 20, 2025 •

5min read

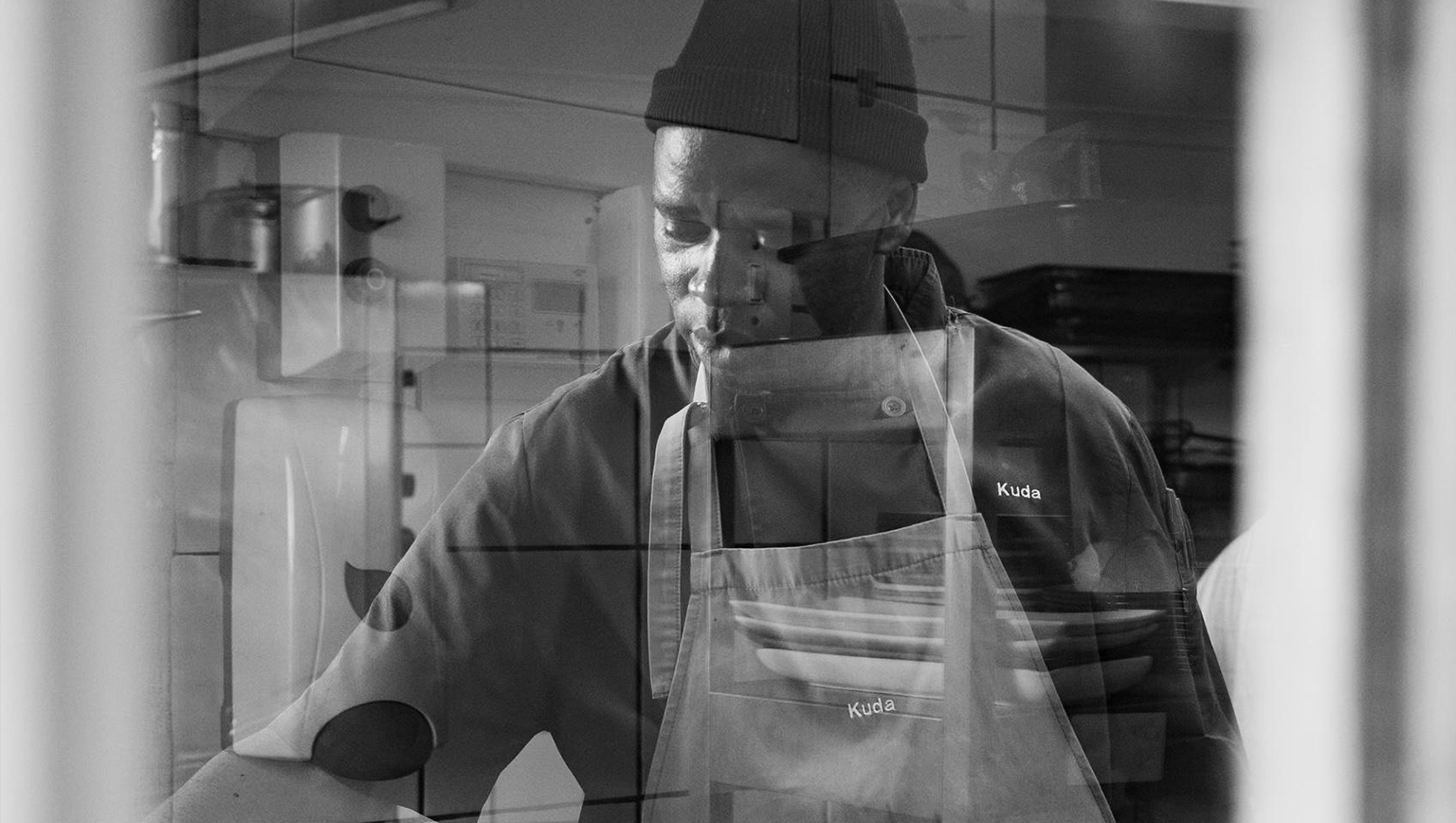

Cape Town Flavors: The Inspiring Journey of Chef Kuda at Judd's Local

Abigail MacFadden • February 19, 2025 •

5min read

Art Fair Season: What to Watch at Frieze Los Angeles 2025

Abigail MacFadden • February 18, 2025 •

6min read

Sophia Kacimi, French-Moroccan Designer Transforms Luxury Fashion into Chess Art

Abigail MacFadden • February 17, 2025 •

5min read

Dog Day Afternoon

Chiara Padejka • February 14, 2025 •

4min read

Fall/Winter Femme Fatale from Pamella Roland FW25 Collection

M. Marki • February 13, 2025 •

5min read

Frederick Anderson's Fall 2025 Collection: Where '90s Hip-Hop Meets High Fashion

Sasha Bernier • February 12, 2025 •

5min read

From Poetry to Hip-Hop: The Evolution of Fame

Abigail MacFadden • February 11, 2025 •

5min read

Shakespeare Takes Center Stage: Alice + Olivia’s Literary Inspired Fall 2025 Collection

Dominique Aronson • February 10, 2025 •

5min read

Bridging High Art and Popular Culture with “Match with Art’s” Salome

Abigail MacFadden • February 10, 2025 •

6min read

From Ballet to the Bronx: The Inspiring Journey of Chef Sam Lopez

Abigail MacFadden • February 7, 2025 •

5min read

Francesco Arena’s God sculpture Debuts in Thailand’s Art Forest

Abigail MacFadden • February 6, 2025 •

5min read

Fired Up: Why Hot Glass is the Coolest Exhibit in Delray

Chiara Padejka • February 5, 2025 •

5min read

From Portugal to the Big Apple: Lotty Carrington’s Journey to Find her Voice

Sasha Bernier • February 5, 2025 •

5min read

Nai-Ni Chen Dance Company’s Lunar New Year of the Snake

Dominique Aronson • February 3, 2025 •

4min read

Singing in the Rain : 070 Shake Petrichor Tour

Chiara Padejka • February 3, 2025 •

5min read

Francie Cohen: From OCD to Art Basel – How This New School Artist’s Journey Inspired Divinity Magazine for Women and Non-Binary Voices

Tessa Almond • January 31, 2025 •

5min read

Made in L.A.: Rising from the Ashes the Hammer Museum’s Biennial Moves Forward

Abigail MacFadden • January 29, 2025 •

5min read

Movie Review: A Complete Unknown

Abigail MacFadden • January 21, 2025 •

4min read

“Serendipitous: A New Group Making Noise in Bushwick”

Abigail MacFadden • January 17, 2025 •

4min read

Sins and Sacrifice: Emma Katherine Hepburn Ferrer's Journey Through Sacrifice and Redemption

Abigail MacFadden • January 16, 2025 •

5min read

Uncle Waffles: Amapiano's Global Ambassador Lights Up Cape Town

Sasha Bernier • January 15, 2025 •

3min read

Enzo Ishall: How Zimbabwe's Dancehall King Transformed Jamaican Music into Zimhall | Live Show Review

Sasha Bernier • January 6, 2025 •

3min read

Lauren Whitfield: Texas Poet Combines Yoga, Writing, and Healing Through Innovative Poetry Workshops

Abigail MacFadden • January 2, 2025 •

4min read

Don't Be Mad: Miller's Art Basel Journey from Houston to Miami Beach

Abigail MacFadden • December 30, 2024 •

4min read

From St. Barth to Art Basel: Inside Karolina Karlsson's Muted Gemini Series and Work Wives

Abigail MacFadden • December 27, 2024 •

4min read

When Eden Gets an AR Upgrade: Oriana Pirela for Creativo

Chiara Padejka • December 24, 2024 •

6min read

Creativo's Garden of Eden: Anastasia Butacova in Full Bloom

Chiara Padejka • December 20, 2024 •

5min read

Adam and Eve: The Origin Story of Creativo

Sasha Bernier • December 4, 2024 •

5min read

Fruit Ninja IRL: Luis Gonzalez Carves Out a Fruitful Endeavor

Chiara Padejka • November 26, 2024 •

5min read

Forbidden Fruit Couture: Dressing the Garden of Eden at Art Basel

Abigail MacFadden • November 21, 2024 •

3min read

Bloom: An Expression of Womanly Resilience

Tessa Almond • November 13, 2024 •

5min read

The Art of Giving Shines at Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation’s 26th Angel Ball

Mariele Marki • November 1, 2024 •

4min read

Innovation Through Collaboration: The Saphira Ventura Gallery Story

Abigail MacFadden • October 31, 2024 •

4min read

Africa's Art Market: Emancipation, Innovation, and Global Impact

Lara Sleiman • October 26, 2024 •

4min read

Woven Paintings and Human Migration: Clement Denis Exhibition at Chelsea's Nicolas Auvray Gallery

Abigail MacFadden • October 24, 2024 •

4min read

Textile, Texture, and Transformation: Innovative Voices in Contemporary Art

Abigail MacFadden • October 22, 2024 •

5min read

Art Basel Paris Guide: Can’t Miss Booths and a new James Turrell!

Abigail MacFadden • October 17, 2024 •

5min read